Compiled by Jean Adele Roth

Irish Special Interest Group – Seattle Genealogical Society and Library

THE INITIAL INVASION OF IRISH: Since the beginning of settlement, migrations in both directions between Britain and Ireland had occurred. Gaels from Ireland colonized South-West Scotland replacing the native Picts. The Normans, who came in 1189, began more than 700 years of English involvement. Colonization by the British was a disaster, especially for poor Irish Catholics. It was a sustained effort of British Colonialism in Ireland for the last 400 years that badly affected both the creation and survival of many records used by genealogists.

You MUST understand Ireland’s history to be successful in your research.

TUDOR RE-CONQUEST OF IRELAND: England’s King Henry VII began the Tudor “re-conquest” of Ireland and gained the submission of the Gaelic chieftains by promising that they would retain lordship of their ancestral territories. He also tried destroying Gaelic culture. The Irish resisted denial of the Pope’s authority. Queen Elizabeth I finished what her father had started. The English authorities tried to extend their authority over Ulster, the most Gaelic part of Ireland, in the Nine Years War of 1594-1603. It ended with the surrender of the O’Neill and O’Donnell lords to the English crown. The imposition of English law, language and culture, as well as the extension of Anglicanism as an institutional religion was intolerable. The “Flight of the Earls” began on 14 September 1607 with ninety of their followers escaping to the Continent.

THE PLANTATION PERIOD in ULSTER – the SCOTS-IRISH: King James VI of Scotland and England gained possession of the Kingdom of Ireland. The 16th and early 17th century English conquest was marked by large scale “Plantations,” in Ulster and Munster so small colonies of English settlers could provide model farming communities on confiscated lands. Six counties were involved: Armagh, Fermanagh, Cavan, Coleraine, Donegal, and Tyrone. The result was the establishment of central British control. Irish culture, law and language were replaced; and many Irish lords lost their lands and hereditary authority. Land-owning Irishmen who worked for themselves suddenly became English tenants. The Plantation system eventually degenerated into a series of atrocities against the local civilian population before finally being abandoned.

THE IRISH REBELLION OF 1641: The failed Rebellion of 1641 by Irish Catholic gentry developed into an ethnic conflict between native Irish Catholics, and the English and Scottish Protestant settlers. The rising was also sparked by fear of an impending invasion of Ireland by anti-Catholic forces of the English Long Parliament and Scottish Covenanters. In turn, the rebels’ suspected association with the pro-Catholic King Charles I helped to spark the outbreak of the English Civil War. In Ulster, there were widespread attacks by the native Irish on the English Protestant settlers. Up to 12,000 Protestants lost their lives, the majority dying of cold or disease after being expelled from their homes in the depths of winter. In the long term, the killings committed by both sides in 1641 intensified sectarian animosity.

THE CROMWELLIAN & WILLIAMITE WARS (1650’s – 1690’s): England’s King Charles I religious policies enraged reformed groups like the Puritans. The monarchy was abolished and Charles was executed for high treason. A republic was formed called the Commonwealth under the anti-Catholic Oliver Cromwell. In 1649, Cromwell landed in Ireland and mass killings completed the conquest. In the 1652 Act of Settlement, anyone who held arms against Parliament forfeited all their lands. The Irish chieftains who would not conform were given the choice of going “to Hell or to Connaught.” This western Irish province had the poorest land in Ireland. The Irish Catholic land-owning class was utterly destroyed. The Jacobite defeat in the Williamite War led to more land confiscations. The late 17th century saw another major wave of settlers into Ulster by tens of thousands of Scots who fled a famine in Scotland.

THE SCOTS-IRISH COME TO AMERICAN COLONIES: In your research you must determine what kind of Irish you are. If your ancestors came to America in the 1700’s, they were primarily Scots-Irish (Ulster Scots). Some of the Scots-Irish had little or no Irish ancestry at all, as dissenter families had also been transported to Ulster from northern England, Wales, the London area, Flanders, the German Palatinate, and France. These different national groups were united by their common Calvinist beliefs, and their separation from the established Churches of England and Ireland. From 1710 to 1775, over 200,000 people emigrated from Ulster to the 13 Colonies, from Maine to Georgia. The largest numbers went to Pennsylvania. From that base, some went south into Virginia, the Carolinas and across the South, with a large concentration in the Appalachian region; others headed to western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and the Midwest.

The American Revolution: The Scots-Irish who came to America in the 1770’s were ardent supporters of American Independence. North Carolina, with its large Scots-Irish population, made the first declaration for independence. Irish emigration was halted by the American Revolution, but resumed after 1783, with a total of 100,000 arriving in America between 1783 and 1812. With the Industrial Revolution, they settled in industrial centers, where many became skilled workers, foremen, and entrepreneurs. There were 400,000 U.S. residents of Irish birth or ancestry in 1790.

Ulster-Scottish Canadians: The first significant Canadian settlers from Ireland were Ulster Protestants, largely of Scottish descent who settled in central Nova Scotia. Protestant Irish, both Irish Anglicans and Ulster-Scottish Presbyterians, migrated over the decades to Upper Canada (now Ontario), some as United Empire Loyalists. Ulster-Scottish migration to Western Canada has two distinct components – those who came via Eastern Canada or the U.S. and those who came directly from Ireland. A group of Scottish and Irish colonists settled in Manitoba. Many “English” Canadian settlers were Irish loyalist Protestants or members of the Orange Order.

ANTI-CATHOLIC LEGISLATION and the PENAL LAWS: From the 15th through the 19th centuries, successive English monarchies and governments enacted laws designed to suppress and destroy Irish manufacturing and trade, and to govern the conduct of Irish Catholics. These discriminatory Penal Laws deprived Catholics of all civil life; reduced them to a condition of most extreme and brutal ignorance and dissociated them from the soil. The violence of the 17th and 18th centuries, created an increasingly dangerous polarization between Ireland’s Catholic and Protestants. Many landholding Catholic families converted to the Church of Ireland to retain their rights. The Penal Laws were one reason for the scarcity of priests and disorganization of parishes. Surviving Catholic and Presbyterian Church registers generally only date from the 19th century.

THE ROAD TO IRISH INDEPENDENCE: Liberal elements among the ruling class were inspired by the example of the American Revolution (1776-1783) and sought to achieve reform and greater autonomy from Britain. When France supported the Americans in their War, London called for militias to defend Ireland against the threat of invasion from France. Many thousands joined the Irish Volunteers. In 1782, they forced the Crown to grant the landed Ascendancy self-rule and a more independent parliament. The Orange Order was founded in 1795, with its goal of upholding the Protestant faith and loyalty to William of Orange and his heirs.

THE IRISH REBELLION of 1798: The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was an uprising by the United Irishmen, led by Theobald Wolf Tone, calling for the establishment of a republic in Ireland. Many civilians were murdered by the military, which also practiced gang rape, particularly in County Wexford. Individual murders were also unofficially carried out by aggressive local militia.

THE ACT OF UNION of 1801: The Act of Union came into effect on 1 January 1801 and took away the measure of autonomy granted to Ireland’s Protestant Ascendancy. The Irish Parliament was abolished and Ireland became part of a new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

ROBERT EMMETT’S REBELLION: After the 1798 rising, Robert Emmett tried to reorganize the defeated United Irish Society. A warrant was issued for his arrest. He escaped to the continent to secure military aid from Napoleon. Commanding the United Irishmen, he led an abortive rebellion in 1803. He was betrayed, captured and tried for high treason. At only 25, he was publicly hanged, drawn and quartered. As he waited to die, Emmitt delivered his famous Speech from the Dock: “Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance, asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace, and my tomb remain un-inscribed, and my memory in oblivion, until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done.”

THE TITHE WAR OF 1831: All land owners, regardless of their religion, were required to pay an annual tithe of 10% of their agricultural produce to the Anglican Church of Ireland. In the Tithe War of 1831-1836, many people refused. There are records of those who refused – most who would later be affected by emigration and the famine. There are 30,000 names with complete records for 232 parishes. Some counties and parishes are missing.

THE POTATO FAMINE – THE GREAT HUNGER: The Irish Potato famine of the 1840’s was one of the worst disasters in world history. By the early 1840’s, almost one-half of the Irish population depended almost exclusively on the potato for their diet. The potato was packed with vitamins resulting in an enormous growth in population – from 3 million in 1800 to 8 million in 1845. A farmer could grow triple the amount of potatoes than grain on the same plot of land. A single acre of potatoes could support a family for a year. Part of the crop was sold to pay the rent and supplies, the rest was for food. A devastating plant fungus arrived accidentally in 1845 from Mexico and crossed Europe. When it reached Ireland, it destroyed the potato crop. With one of the coldest winters in Irish history, poverty-related diseases such as typhus, jaundice, scurvy, cholera, dysentery, and infestations of lice became widespread. Observers reported children crying with pain and looking “like skeletons, their features sharpened with hunger and their limbs wasted, so that there was little left but bones.” The starving and sick crowded into towns in the hope of securing help. Ireland, the beautiful country with some of the best farm land in the world, became a place that was littered with bodies and abandoned villages.

While the British did not cause of the Famine, they certainly were the reason so many people died. Britain’s economic policy was “laissez-faire” (meaning “let be”) which held that it was not a government’s job to provide aid for its citizens, or to interfere with the free market of goods. The British Government felt the problems arose from Ireland’s perennial rebelliousness and from the swarming, poverty-stricken “surplus” population, as it was called, that absorbed the attention of Parliament. The British failed to take swift and comprehensive action in the face of Ireland’s disaster. It is time to stop using the euphemism “Irish Potato Famine” for two reasons. First, there was no shortage of food in Ireland. There were eight ships a day filled with food being exported to England. Secondly, it was not simply a “famine” but a starvation based on systematic British exploitation of the Irish people, inaction in the face of the potato crop failure, and a vindictive, racist attitude toward the Irish. Nearly two million died out of a population of eight million. Frank O’Conner noted: “Famine is a useful word when you do not wish to use words like genocide and extermination.” In 1861, John Mitchell wrote: “The Almighty indeed sent the potato blight but the English created the famine.” He observed that “a million and a half men, women, and children were carefully, prudently and peacefully slain by the English government. “

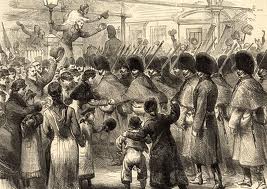

EVICTION: Laws passed by the British Parliament intended to help the poor became part of the problem. The Poor Law Extension Act made landlords responsible for the maintenance of their own poor. When peasants were unable to pay rent, the landlords soon ran out of funds with which to support them. In the early years, many landlords reacted with compassion, some reducing rents. A way around the Poor Laws was eviction. The farmers paid rent by working the land, but could be evicted without notice. If a landowner had no tenants on his land, what responsibility would he have? Tenants were helpless as their tiny homes were destroyed to make sure that they couldn’t come back as squatters. Starving people with their possessions on their back, walked with their children to nowhere. Many dropped dead on the roads. Some tried to shelter their families by building a lean-to or living in holes dug in the Irish bog. Whole villages of healthy peasants were turned into starving, rag-clad people for whom death became a relief. Landlords evicted hundreds of thousands of peasants, who crowded into disease-infested workhouses.

WORK HOUSES: A series of work houses had originally been established to provide for Ireland’s destitute. Under the Poor Law act of 1838, each Poor Law Union was required to maintain a workhouse where local paupers could be fed and housed. By 1845, there were 130 of them. The conditions were so bad and the rules for entry so strict that people would only go to them as a last resort. Families were torn apart and children were separated from the adults. Work houses soon became filled to capacity. Many starving people were turned away. Some 2.6 million Irish entered overcrowded workhouses, where more than 200,000 died. In the spring of 1847, Britain tried to cope with the famine, setting up soup kitchens and programs for emergency work relief. But, many of these closed when a banking crisis hit Britain. It was not characteristic for England to behave as they did in Ireland. As a nation, the English have proved to be capable of generosity, tolerance, and magnanimity – but not where Ireland was concerned.

DEATH without DIGNITY: Death descended on the Emerald Isle as starvation and disease killed thousands. By 1847, witnesses reported there were unattended bodies by the roadside and in homes. Some people were dead as long as 11 days before they were buried. Burdened beyond their capacity, coroners stopped holding inquests for people who died in the streets. Some dead were buried where they died, in fields, or on the side of the road. People were dying so fast that mass graves were left open to receive corpses.

There was no one or no time to keep records.

IRISH IMMIGRATION: – 19th Century: Emigration was a long term legacy of the famine. Over a million people emigrated to Britain and North America. Most were Native Irish and Catholic. Ship owners crowded hundreds of desperate Irish onto rickety vessels. The majority of the emigrant ships were small, ill-equipped, dangerously unsanitary, and often unseaworthy. They became known as “coffin ships.” Some never arrived, those that did carried passengers already infected with and dying of typhus. Many ships reached port only after losing a third of their passengers to disease and hunger. Sharks followed in the wake. Although they left Ireland for a myriad of reasons – all the emigrants had one thing in common – hope. Their experiences varied but for those who made it – the first night in America was better than the last night in Ireland. Still, arrival in America meant more hardship. The Irish who managed to reach this country had little or no money and were often too weak to work. They crowded into cellars without light or sanitation, begged in the streets, and accepted whatever employment they could get at poor wages. Irish immigrants came to be regarded as a danger to the health of the community and a burden on society. Between 1848 and 1864, thirteen million pounds was sent home to Ireland by emigrants to bring relatives out, and it is part of the famine tragedy that a steady drain of the best and most enterprising left Ireland to enrich other countries.

HOME RULE: Since the 1880’s, Irish nationalists had demanded Home Rule or self-government, from Britain. Fringe organizations, such as Sinn Féin argued for some form of Irish independence, but they were in a small minority at this time. Home Rule was eventually granted by the British Government in 1912, immediately prompting a prolonged crisis within the United Kingdom as Ulster Unionists formed an armed organization, the Ulster Volunteers, to resist. In turn, Nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers. The British Parliament passed the Third Home Rule Act with an amending Bill for the partition of Ireland but the Act’s implementation was postponed by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. The majority of Nationalists followed the call to support Britain and the Allied war effort in Irish regiments of the New British Army. But, a significant minority of the Irish Volunteers opposed Ireland’s involvement in the war.

THE EASTER RISING: Most Protestants in Ulster did not want “Home Rule” so Irish groups, like Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers formed to fight. On April 24, 1916, the “Easter Rising” began by the Irish Volunteers and an Irish citizen army, with the support of the Fenians. The rebel headquarters was located at the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin. They hoisted two republican flags and Patrick Pearse read a Proclamation of the Republic. The Rising was put down within a week by British Forces. A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested. The leaders were thrown into Kilmainham Jail. Fifteen of the ninety people sentenced to death, including all seven signatories of the Proclamation, were brutally executed by firing squad. Some Rising survivors became leaders of the independent Irish state. The Easter Rising had far-reaching effects on Ireland’s subsequent history. The majority of the casualties were civilians.

IRISH CIVIL WAR: The fight for Irish Independence would prevail with the subsequent Irish Civil War. The British responded to the escalating violence with force. They set up paramilitary police units like the “Black and Tans.” Seven thousand strong, they were mainly ex-British soldiers demobilized after World War I. They rapidly gained a reputation for drunkenness and ill-discipline. In response to IRA actions, in the summer of 1920, the “Tans” burned and sacked numerous small towns throughout Ireland. On 9 August 1920, the British Parliament passed the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, which suspended all coroners’ courts and replaced them with “military courts of inquiry.” The violence escalated steadily until July 1921. The separatist Sinn Féin party won a majority of seats in Ireland and set up the first Dáil (Irish Parliament) in Dublin. Their victory was aided by the threat of conscription into the British Army.

PARTITION: Before the formation of the Republic of Ireland and the separation of the six counties of Northern Ireland which remained a part of the United Kingdom, it was all just “Ireland.” In December 1922, the Parliament of Northern Ireland exercised its right from the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 to opt out of the newly-established Irish Free State. The descendants of the British Protestant settlers largely favored a continued link with Britain. The descendants of the native Irish Catholics wanted Irish independence. When partition occurred – only six counties were included in the Northern State which ensured that there was a permanent Protestant majority. Privileges were handed out to Protestants in the form of jobs and houses. The Protestant bosses owned the factories and made sure that only Protestants were employed in them.

DESTRUCTION OF RECORDS: There is a long history of the destruction of historic Irish records, including a fire in the Custom Office in 1711, and another in the Birmingham Tower in Dublin Castle in 1758. Unfortunately, the

records were not comprehensively indexed, so we do not know what was lost but the main records stored there were the legal, financial, and administrative records of the 13th to the 17th centuries. British colonialism also affected the survival of historic records because of differences between Ireland and Great Britain, in how the records were made and kept. In 1914, the British government ordered that the Census of Ireland returns from 1861 to 1891, be pulped to create paper for the war effort.

Custom House: As the port of Dublin moved further downriver, the building’s original use for Ireland. During the Irish War of Independence, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) burnt down the Custom House in an attempt to disrupt British rule in Ireland. The central dome collapsed, causing the destruction of centuries of irreplaceable Irish records in the Custom House in 1921.

Public Records Office: The destruction of the Public Records Office of Ireland in Dublin’s Four Courts on 13 April 1922 is the most famous archival disaster in Irish History. The PRO was the repository of the majority of administrative records of Ireland from the 14th century on. It was used as an ammunition store by the anti-Treaty side in the civil war. Hit by a shell fired by the pro-Treaty forces, it exploded one thousand years of Irish state and religious archives – including the surviving 19th century census returns between 1821 and 1851, more than half of all parish registers of the Anglican Church of Ireland; and the majority of wills and testamentary records proved in Ireland to that date. Only the records in the Reading room survived. These included non-Church of Ireland parish records, civil records of births, marriages and deaths, property records and later censuses. For some material that was lost, there are abstracts, transcripts and fragments of the originals. Although most of the prerogative wills were destroyed, Sir William Betham, Ulster Kling of Arms, provided a valuable substitute. He took genealogical notes from virtually all of the prerogative wills from 1536 to 1800 and formed them into pedigree charts.

END OF THE CIVIL WAR: Despite acceptance of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922, which confirmed the future of Northern Ireland, there were clashes between the IRA and British forces. The treaty to sever the Union divided the republican movement into anti-Treaty supporters led by the former president of the Republic, Eamon de Valera, who wanted to fight on until an Irish Republic was achieved and pro-Treaty supporters who accepted the Free State as a first step towards full independence. The civil war ended in mid-1923 in defeat for the anti-treaty side, and cost the lives of many leaders of the independence movement, including Michael Collins, who was assassinated in 1922. The new Irish Free State quietly ended its overt violent aggression towards Northern Ireland. The total number killed in the war came to over 1,400. In 1937, a new Constitution re-established the state as Ireland (or Eire in Irish). The State remained neutral throughout World War I although tens of thousands volunteered to serve in the British forces. In 1949, Ireland was formally declared a Republic and left the British Commonwealth.

“THE TROUBLES”: The history of Northern Ireland has been dominated by sectarian conflict which erupted into the “Troubles” in the late 1960’s, until an uneasy peace with the Belfast “Good Friday” Agreement of 1998. Violence continues on a sporadic basis. The “Troubles” participants included republican and loyalist paramilitaries, the security forces of the United Kingdom and of the Republic of Ireland and politicians and activists on both sides.

MODERN IRELAND NOW: The Irish Penal Laws, the Potato Famine, the fight for Independence, Partition, and “The Troubles” left lasting feelings of bitterness and distrust toward the British. There is an uneasy peace at best in Northern Ireland. The resentment of the British Colonialism and barbaric domination over the Irish continues to this day. It is not just a religious issue, but a total lack of comprehension that has manifested itself in prejudice, destruction and death as well as a complicated political, religious, and social history.

Jean A. Roth is a retired Certified Travel Consultant and has been an active genealogist with the Seattle Genealogical Society since 1977 – researching her German, Irish, and English ancestry. She is an Honorary Life Member and has served the Society as President and Director of Education. She is the current SGS Vice-President and Group Leader for the Irish and German Special Interest Groups. She also serves on the Board of Seattle’s Irish Heritage Club as a genealogical advisor. Jean is a Life Member of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia and is the Greater Seattle Chapter’s President. She serves on the National AHSGR organization as a Village Coordinator and Historian for her paternal ancestral village in Russia’s Volga River region.

Pingback: The Horses of Ballyfermot – The Circular

Pingback: The Horses of Ballyfermot – James' scroll

I’m from India. The depredations the Irish suffered under British rule are very similar to what the people in the subcontinent did. I saw a documentary on the Irish famine which looks artificially similar to Bengal famine in 1943. At least you people were genetically related to them (whites) but they still chose to treat you in such a barbaric manner. What this means is the British Anglo-Saxon ruling classes have a pact with the devil. They cannot be human beings given how much brutality and torture they’re capable of. Fortunately, the UK is a second-rate declining power today. The current generation of Brits will pay for the sins of their ancestors while the country slips into mediocrity and irrelevance.

Irish people were the largest ethnic group in the British Army during the 19th century, probably forming between 40%-45% of the membership. Without any doubt, these Irish brutally repressing rebellions by the indigenous peoples as their England-Scotland fellows did.

No matter how you hate it, the colonial legacy of British rule is a part of Modern India. Your political system are inherited from British common law, the only language be used for communication between many different ethnic groups is English. Without this legacy, there will be no Modern State as India & Pakistan- Bangladesh but a bunch of divided states slips into mediocrity and irrelevance.

Dear Sirs,

RE: PROMOTING THE CONCEPT OF A NORTHERN IRISH BILL OF RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS

This publication may be of interest to you via Kindle eBooks

£3.40 GBP View on Amazon

What is this e-book about?

The Anglo-Irish / NI conflict did not take place in a vacuum. There has been an ongoing historic conflict from the early European tribal settlements onto these islands. Extending to a settled totality in the context of emerging conflicting and competing cultural identities. In essence, at the commencement of the latest Anglo-Irish / NI conflict, on a final analyses, all that existed were the oppressors and their agents / hostages, the oppressed and those who resisted oppression. No one was neutral everyone took a side during the conflict, whether they were active, passive or ambivalent? At the end of this particular conflict, all that emerged was a set of outcomes, to include a death toll, as to who had been killed, permanently injured either physically or emotionally or both; those who had allowed themselves to be owned by the empowered authorities, those who were the victims of emotional cowardice and or let themselves down, those who made the conflict about themselves, those who profited from the conflict, those who have been permanently criminalised for life; those who have been allowed to live. The only consolation was the signing of the Belfast Agreement / Peace Treaty? The prime objective of the Belfast Agreement was as a peace treaty; structured to accommodate a constructed ambiguity at variance with facilitating social cohesion and community integration and open to political sophistry in an institutional and community situational positioning in an inconclusive political and cultural struggle.

The central theme running through this publication is a transitional justice approach and the aim is to establish a statutory entrenched, Northern Irish Home Rule Bill of Rights and Freedoms. There is a continuous thread intent on protecting and preserving the integrity of the Northern Irish system of jurisprudence based on the common law of England. The Anglo-Irish / NI conflict resolution process is dependent on this thread as an enabling transitional justice mechanism, underpinning constitutional and institutional change in assisting a society emerging out of conflict. The aims and objectives of a transitional justice approach to a managed change process, is to build on the Belfast Agreement / Treaty, by incorporating the Belfast agreement and the constitutional principles contained therein; together with the agreed institutions supporting democracy into a statutory entrenched NI Home Rule Bill of Rights and Freedoms. A set of protective rights, specific to a new Northern Irish Home Rule State, relating to perceived superior absolute constitutional and inherent cultural human sovereign rights and freedoms; A set of NI citizen freedom of choice optional rights aimed at assisting situations involving competing and conflicting rights. In particular, in relation to Christian conscience, equality of treatment, and the citizens freedom of choice optional rights; the European convention on human rights and freedoms 1950; and a standard set of civil and human rights; a Canadian style notwithstanding clause; a set of social, economic imperative rights. The proposed NI Home Rule Bill of Rights blueprint, will be supported by the adoption of a set of proposed peace process conceptions, incorporated into a Declaration by HMG and the Government of Ireland and into a Preamble to the Bill of Rights and Freedoms, establishing the entrenchment of the concept of Northern Irish constitutional sovereignty, as distinct from national sovereignty, supported by a Northern Irish supremacy law clause. This transitional justice approach is assisted by a perusal of the processes of managed constitutional change in other rule of law democracies with a jurisprudence based on the common law of England. Regrettably, the partition of Ireland, fifty years of a semi-apartheid Northern Irish State, thirty years of conflict and twenty one years of the Belfast agreement. This peace process has stalled short of fully implementing the Belfast Agreement? In particular, an agreement to a Northern Irish Bill of Rights, mandated by the Belfast Agreement? The peace process is in danger of collapsing, if Northern Ireland is taken out of EU / CU / EEA without entrenching a transitional justice NI Bill of Rights and Freedoms, which will for the most part solve many of the outstanding issues. Thereby, enabling the business of Northern Irish governance to go forward with the option to work towards social cohesion and community integration.

Kind Regards,

John A Coyle BA (Econ). BSc (Hons). BSc (Hons) Psych., L.LM.

Pg. D. L. S., / Dip Laws (CPE / LSF) – Commissioner for oaths.

Pg. H. Dip. Adult & Community Ed. (NUI), QTS (FE), MBPsS

Pingback: Breeding Contempt for the Familiar: Colonizing and Othering the Irish – Melannie Wurm

Pingback: The Ultimate Ireland Guide - What A Wonderful Week